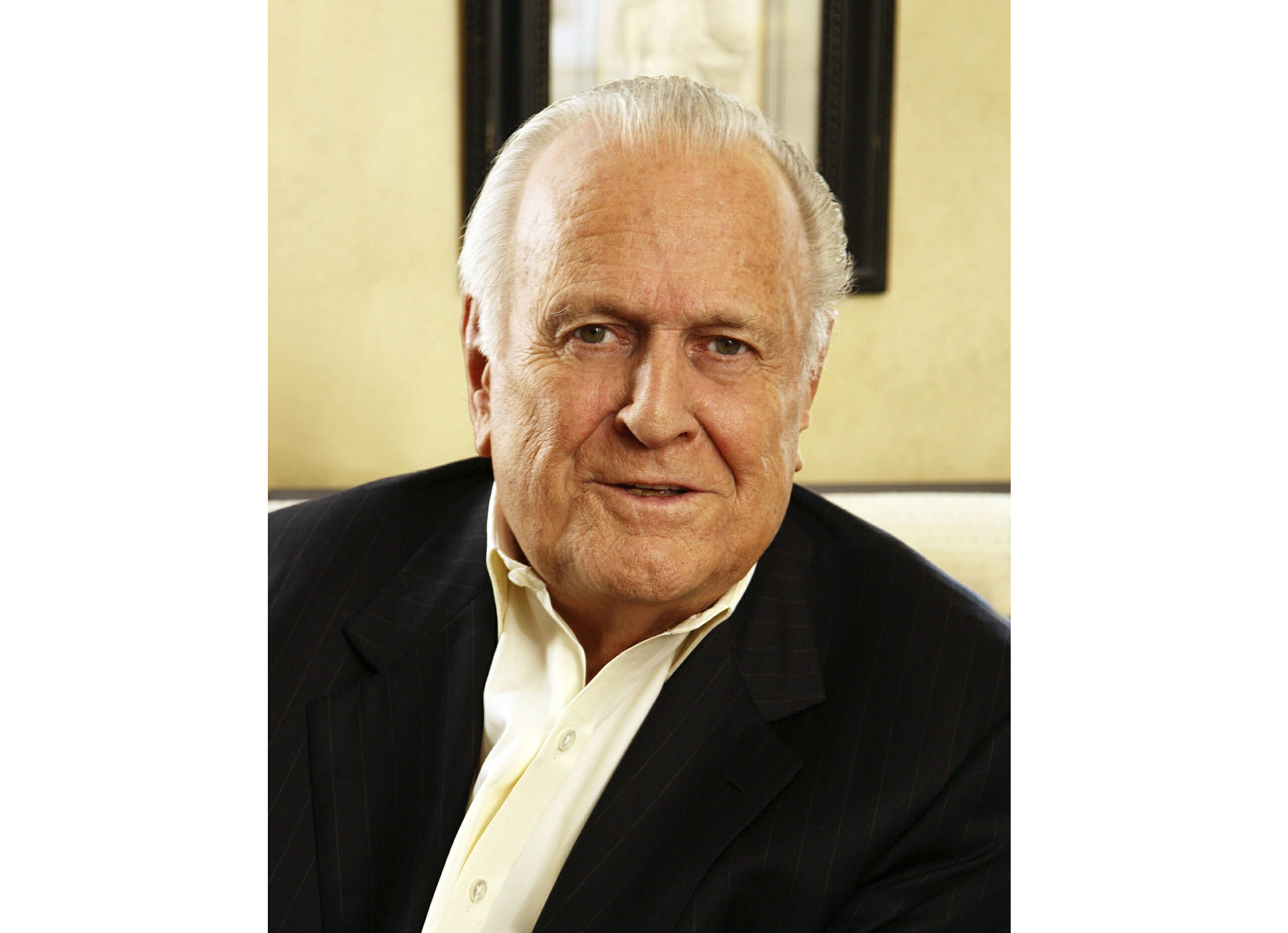

John Richardson, critic and Picasso biographer, dies at 95

NEW YORK (AP) — Sir John Richardson, the eminent historian and critic whose multivolume series on Pablo Picasso drew upon his personal and aesthetic affinity for the Spanish painter and was widely praised as a work of art in its own right, has died. He was 95.

Nicholas Latimer, a vice president and senior director of publicity at Alfred A. Knopf, said Richardson died Tuesday morning at his Manhattan home.

The London-born Richardson’s first Picasso book, “A Life of Picasso: The Prodigy, 1881-1906” came out in 1991, and was followed by editions covering 1907-1916 and 1917-1932. Latimer said that Richardson had been well into a fourth volume, in the works for over a decade. But he did not immediately know the title, what years it would cover or when it would be published.

Art lovers had looked forward to Richardson’s Picasso writings the way readers of politics have anticipated Robert Caro’s Lyndon Johnson series. Like Leon Edel’s five-volume epic on Henry James and Richard Ellmann’s “James Joyce,” Richardson’s books were regarded as biographies of the highest literary quality, graced by knowledge, poetry, passion and insight. Richardson’s criticism and scholarship brought him a Whitbread Award in 1991, election to the British Academy two years later and a knighthood in 2012.

Reviewing Richardson’s third Picasso volume, in 2007, The New York Times’ Michiko Kakutani cited Richardson’s “intimate understanding of the artist’s temperament and endlessly inventive styles, his expansive vocabulary of myths and motifs and, most important, the mysterious nature of the alchemy by which he transformed his own experiences and emotions into art.”

Richardson had admired Picasso’s work since he was a teenager, when he failed to convince his mother to lend him $250 so he could buy “Minotauromachy” (a black and white print later sold for $1.5 million). He befriended the artist in the late 1940s, while both were living in the south of France, and remained close with him for years.

“It must have been hell to be his child or his mistress but to his friends he was beguiling. There was never a dull moment,” he told The Associated Press in 1991, adding that Picasso seemed inspired by his friends.

“He was like a human cannibal in that way. We’d all be suffering from nervous exhaustion at the end of the day from his intensity and he would have all this energy he seemed to get from us. At the age of 85, he’d go sailing off into studio and work all night long.”

Patrician in his speech and attire, Richardson had lived in New York since 1960 and his 5,000 square foot loft on Fifth Avenue included art by Andy Warhol, Georges Braques and, of course, Picasso, who died in 1973. Among his friends were Warhol, music executive Ahmet Ertegun, Oscar and Annette de la Renta and art dealer Larry Gagosian, at whose galleries Richard helped curate several Picasso exhibitions.

Richardson also wrote for The New Yorker and Vanity Fair and was a board member of the Modern Library, a Penguin Random House imprint that reissues classic works. He served as managing director of the art dealers’ consortium Artemis, founded Christie’s USA and headed the New York-based auction house for nine years.

Born in 1924, Richardson was the son of Boer War commander and Army & Navy Stores co-founder Sir Wodehouse Richardson. His “earliest, indeed happiest memories” were of his father’s business, including a Victoria Street department store where employees treated him as a “little prince” and hung his picture in the elevator.

But when John was just 5, his father died and his mother sent him to a boarding school so “horrendous” that Richardson once “was left dangling by the wrists from a hook in the ceiling, my shrieks disregarded by those in authority.” Mercifully, by age 13 he was attending the humane Stowe public school, which featured a progressive art program that Richardson credited with “triggering an obsession with Picasso.”

He was still a teenager when he decided to become an artist, a dream he would abandon in his 20s, but not before he had befriended Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud among others and helped design a “Britain Can Make It” exhibit at the Victoria and Albert Museum.

For much of the 1950s, he lived in a chateau in France with the art collector Douglas Cooper, who died in 1984. In “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice,” published in 1999, Richardson remembered Cooper as a mentor adventuresome and charismatic, but also spiteful and easily offended. Their relationship was damaged for good after Richardson questioned the authenticity of two paintings allegedly by the French artist Fernand Leger.

“There was a terrible silence, during which Douglas’s pink face turned the color of a summer pudding. ‘What a little expert we’ve become,'” Richardson wrote.

“And then came a shriek like calico ripping — comical but also alarming. ‘How dare you pontificate to me about Leger!’ he yelled. ‘Those paintings are absolutely authentic. Get out, get out.’ And then he took another look at the photographs, and I realized that he realized that I was right and he was wrong. Things would never be the same again.”

The Western Journal has not reviewed this Associated Press story prior to publication. Therefore, it may contain editorial bias or may in some other way not meet our normal editorial standards. It is provided to our readers as a service from The Western Journal.

Truth and Accuracy

We are committed to truth and accuracy in all of our journalism. Read our editorial standards.

Advertise with The Western Journal and reach millions of highly engaged readers, while supporting our work. Advertise Today.