Meet the Woman Who Gave Hundreds of WWI Survivors the Chance To Feel Normal Again

Art helps people see the world in a new way. In World War I, artists like Anna Coleman Ladd, a Boston-based sculptor, uniquely used art to help the world see people in a new way.

Due to military advancements like machine guns and other kinds of artillery, soldiers were coming home from the war with devastating injuries in various forms — loss of limbs, deep wounds and facial deformities.

Efforts by skilled and progressive plastic surgeons were able to reconcile many soldiers’ injuries, but not all were rectifiable under their scalpel. That’s when Ladd would step in and apply her creative talent.

Ladd was inspired by the founder of the Masks for the Facial Disfigurement Department, Francis Derwent Wood. During the war, he discovered that his past artistic training could be used to help the soldiers who plastics surgeons were unable to help.

“My work begins where the work of the surgeon is completed,” he said, according to the Smithsonian Magazine. He began applying his talent to fashion custom copper masks based off of pre-war photos that the soldiers to wear.

His department was set up in the Third London General Hospital in Wandsworth and was nicknamed the “Tin Noses Shop.” His work would soon inspire Ladd to open her own reconstructive mask shop.

Her sculpture work prior to the war was, according to the Smithsonian Magazine, rather unremarkable and generic. She had received her artistic training in Paris and Rome before returning back to the United States where she met her husband, Maynard, who worked as a physician.

When her husband was appointed to oversee the Children’s Bureau of the American Red Cross in Toul, France, Ladd decided that she would also help victims of the war, but with her artistic talent.

After meeting with Wood to gain some insight on how his own mask department was run, she opened up the Studio for Portrait Masks in Paris with the American Red Cross.

One patron described the studio as “a large bright studio.” Ladd and her four associates had worked tirelessly to make sure that the studio was bright, cheery, and welcoming to those who had endured such trauma. They even placed flowers and hung posters throughout.

Ladd was reportedly difficult to work with. Someone who worked with her said, “Mrs. Ladd is a little hard to handle as is so often the case with people of great talent.” Despite that, however, she ran the studio well.

The masks fulfilled two purposes: to ease both psychological pain and social isolation. The soldiers who came to visit Ladd had gone through a level of trauma that most of us could never imagine.

“The psychological effect on a man who must go through life, an object of horror to himself as well as to others, is beyond description,” Dr. Albee, a notable surgeon of the era, said. “It is a fairly common experience for the maladjusted person to feel like a stranger to his world. It must be unmitigated hell to feel like a stranger to yourself.”

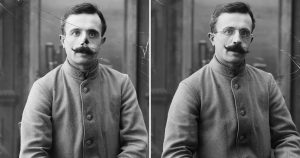

The soldiers that found their way to Ladd’s studio found that the burden of feeling “like a stranger” was lifted after she and her associates worked to construct masks that closely resembled their original faces.

Each mask took close to a month to complete. Once the patient was fully healed they would take a cast of the face and then begin constructing a copper mask that was only 1/32 inch thick.

Ladd and her associates then meticulously painted the masks to match the patient’s skin tone then, using real hair, added eyebrows and other facial hair.

The skin tone was the most difficult part. “Skin hues, which look bright on a dull day, show pallid and gray in bright sunshine, and somehow an average has to be struck,” Grace Harper wrote. “The artist has to pitch her tone for both bright and cloudy weather, and has to imitate the bluish tinge of shaven cheeks.”

Even though the masks were made with excruciating detail, they only lasted for a few years at a time. Ladd wrote about an early patient who continued to wear his mask daily even though it was “very battered and looked awful.”

Ladd’s studio ran from 1917 to 1920, even though she left a year before its close. She and her associates made 185 masks during that time, changing 185 lives. The patients shared immense gratitude to her for helping them regain a sense of normalcy.

“The letters of gratitude from the soldiers and their families hurt, they are so grateful,” she wrote.

One soldier sent her a letter that read, “Thanks to you, I will have a home … The woman I love no longer find me repulsive, as she had a right to do.”

When Ladd left her studio in 1919, her talent and attention to detail were dearly missed as is evident in the studio’s closure soon after. She was later honored as a Chevalier of the French Legion of Honor in 1932 for her charitable acts, seven years before her death in California.

There’s no doubt that Ladd’s work during the war, while small in number, greatly impacted those who were able to receive her studio’s service. She was truly an incredible woman.

Truth and Accuracy

We are committed to truth and accuracy in all of our journalism. Read our editorial standards.