13 People Were Killed and 30+ Wounded at Fort Hood Army Base 10 Years Ago Today

Today is the 10th anniversary of the Fort Hood shooting — when an Army psychiatrist facing deployment opened fire on his colleagues, killing 13 and wounding over 30 more.

In 2011, the Senate released a report calling the massacre “the worst terrorist attack on U.S. soil since September 11, 2001.”

As with any tragic event in history, the Fort Hood shooting is worth revisiting no matter how uncomfortable it may make us feel so that we are reminded of its implications and can honor the innocent lives lost.

Vice President Mike Pence visited the Army base in Killeen, Texas, just last week and stopped by the memorial that has been built to remember those who died in such a senseless act of violence.

“As the 10th anniversary of that terrible day approaches next week, let me say, on behalf of the American people, to the families of our fallen and all you brothers- and sisters-in-arms: The American people are with you, and this nation will never forget or fail to honor the service and sacrifice of our heroes who fell on November 5, 2009,” Pence said on Oct. 29.

“That is my solemn pledge. They and their families will remain in our prayers.”

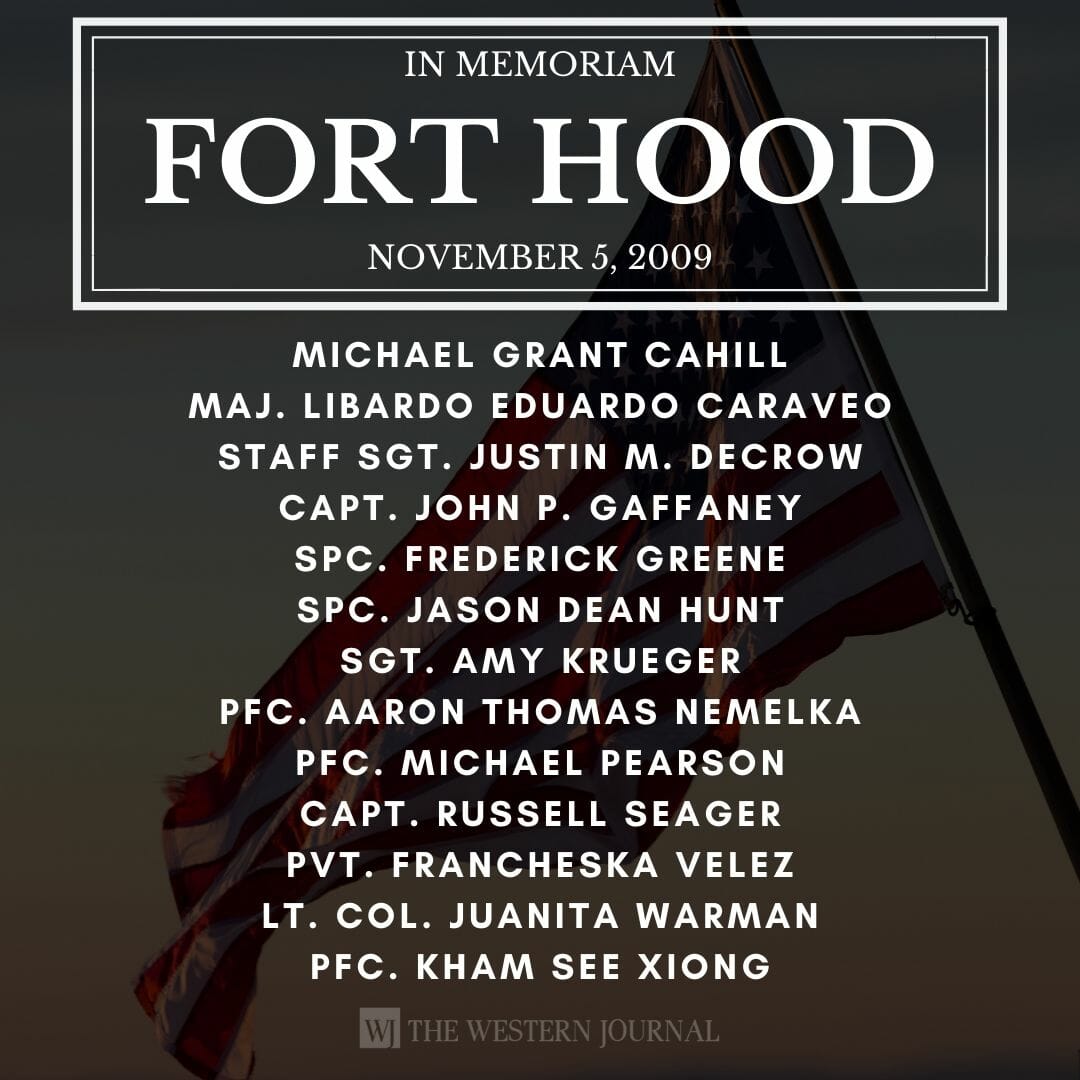

Who are the victims of the Fort Hood shooting?

In alphabetical order of last name, these are the 13 people who were killed as a result of the shooting on Nov. 5, 2009:

Michael Grant Cahill; Maj. Libardo Eduardo Caraveo; Staff Sgt. Justin M. DeCrow; Capt. John P. Gaffaney; Spc. Frederick Greene; Spc. Jason Dean Hunt; Sgt. Amy Krueger; Pfc. Aaron Thomas Nemelka; Pfc. Michael Pearson; Capt. Russel Seager; Pvt. Francheska Velez; Lt. Col. Juanita Warman; Pfc. Kham See Xiong.

What occurred on Nov. 5, 2009, at Fort Hood Army base?

On Nov. 5, 2009, 40-year-old U.S. Army Maj. Nidal Hasan, a psychiatrist, opened fire after shouting “Allahu akbar,” an Arabic phrase that means “God is greater.”

In his rampage, Hasan killed 13 people — 12 military members and one civilian — and wounded 32 others, all members of the military.

One of the men killed that day, 29-year-old Spc. Frederick Greene of Mountain City, Tennessee, suffered from gunshot wounds that indicated he may have tried to charge Hasan in an attempt to stop the attack, according to a Fox News report.

Pvt. Francheska Velez, 21, had just finished a tour in Iraq before she was killed. She was three months pregnant and only weeks away from rejoining her family, according to KXAS.

Hasan only stopped shooting after two civilian police officers confronted and shot him.

“These are men and women who have made the selfless and courageous decision to risk and at times give their lives to protect the rest of us on a daily basis,” then-President Barack Obama said after the shooting.

“It’s difficult enough when we lose these brave Americans in battles overseas. It is horrifying that they should come under fire at an Army base on American soil.”

What do we know about the shooter?

Maj. Nidal Hasan was born in Arlington, Virginia, on Sept. 8, 1970, to a Palestinian couple who had immigrated to the United States, according to The New York Times.

After graduating from Virginia Tech with a bachelor’s degree in 1995, he entered active duty with the U.S. Army.

By 2009, Hasan was a resident in the psychiatric program at Walter Reed Army Medical Center, where he was training to care for soldiers coming home from war.

During his time there, some fellow officers described him as a “ticking time bomb,” according to the Senate report.

His extreme interest in Islamic culture also concerned his colleagues, but during one of his evaluations they described his interest as beneficial rather than concerning, the Senate report noted.

Later, in December 2008, the FBI’s San Diego Office intercepted emails between Major Nidal Hasan and radical imam Anwar al-Awlaki and flagged them as “a product of interest.”

According to Texas Rep. Michael T. McCaul, speaking at a 2012 meeting of a subcommittee of the House Committee on Homeland Security, Hasan told Awlaki about a speaker who defended suicide bombings that prevent the enemy from attacking “his fellow people.”

“‘His intention was to save his people, his fellow soldiers, and the strategy was to sacrifice his life,'” McCaul quoted Hasan as writing. “‘This logic seems to make sense to me.'”

The San Diego office consulted the Washington office to determine to what degree they should investigate, but in June 2009 the Washington office concluded Hasan was not involved in any terrorist activities, McCaul noted.

McCaul argued that if the concerns from Hasan’s colleagues and the suspicious emails had been communicated efficiently between government organizations, the red flags leading up to the event on Nov. 5, 2009, might have been noticed sooner.

“In the Hasan case, both the FBI and DOD had important pieces to the puzzle that, if put together, maybe just could have possibly saved the lives of 12 soldiers and one civilian,” he said.

Was this an act of terrorism or an act of workplace violence?

Even though the Senate called the incident “the worst terrorist attack on U.S. soil since September 11, 2001” in a 2011 report, Hasan’s case was tried as an act of workplace violence.

Because the case was not considered an act of terrorism, the victims were ineligible to receive certain benefits, including the Purple Heart medal.

In 2015, however, victims of the shooting finally received the Purple Heart or Defense of Freedom medal.

“For the recipients of today’s awards, both living and deceased, today is about victory,” retired Army Gen. Bob Cone said during the ceremony. “Today is about fully documenting and acknowledging your sacrifice for this great nation.”

In documents Hasan released to Fox News in April 2013, he renounced his “oaths of allegiances” to anything other than those mandated in Islam, including his “oath of U.S. citizenship.”

During his court martial, Hasan claimed his reason for shooting his colleagues on Nov. 5, 2009, was to stop the military members from going to Afghanistan and killing his fellow Muslims.

Ultimately, he said he was on the “wrong side” of the war in the American military and switched sides, according to The Associated Press.

Scott L. Silliman, a military law expert, said that the Uniform Code of Military Justice does not have an article for “terrorism,” which is why Hasan’s case wasn’t treated that way.

“They really didn’t have an option,” he told the AP. “He was an active-duty officer. The crime occurred on a military installation.”

“Now, if the crime had occurred off the post, then there might have been what we call concurrent jurisdiction between the civilian authorities and the military authorities.”

In August 2013, Hasan was convicted of 13 counts of murder and 32 counts of attempted murder and was later sentenced to death.

He is currently incarcerated on death row at Fort Leavenworth in Kansas, according to KHOU, because military death penalty cases require several appeal stages and could take anywhere from 10 to 15 years to settle.

Truth and Accuracy

We are committed to truth and accuracy in all of our journalism. Read our editorial standards.

Advertise with The Western Journal and reach millions of highly engaged readers, while supporting our work. Advertise Today.