Brawl suits against Turkey raise questions of law, diplomacy

WASHINGTON (AP) — Turkey’s leader spoke of cooperation with the United States during a White House visit two years ago with President Donald Trump, but by day’s end, the warm rhetoric had been overshadowed by a violent brawl outside the Turkish Embassy that left anti-government protesters badly beaten.

That altercation on May 16, 2017, led to criminal charges against some of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s security officers and civilian supporters. It also spurred lawsuits, now winding their way through federal court, that turn on the question of whether a foreign country can be held responsible in American courts for violence done on its behalf.

One suit goes further, saying the violence meets the legal definition of international terrorism because it was designed to coerce and intimidate a civilian population.

“Nobody expects that security forces from a foreign government will come over and beat them to a pulp, and that’s the part that’s really crazy,” Agnieszka Fryszman, a lawyer for the injured protesters, said in an interview.

The suits have diplomatic implications and raise questions about how much legal protection should be extended to the people who protect international leaders from raucous demonstrations when they travel abroad. The legal cases are unfolding as the NATO allies are at odds over a number of issues, including what role Turkey will play in northern Syria as American forces withdraw. The U.S. also has warned Turkey against proceeding with its purchase of an advanced Russian air defense system; the deal, if completed, may incur U.S. sanctions

Turkey has signaled it will argue that, as a sovereign nation, it is immune from being sued, a position that sets the stage for legal and geopolitical wrangling. The strength of Turkey’s argument may depend in part on the severity of the assault and the extent of the violence, said Ingrid Wuerth, a professor of international law at Vanderbilt University.

No one would think it legally acceptable if foreign security officers fatally shot protesters, Wuerth said, “but on the other hand, they probably shouldn’t be liable if maybe all they did was just push someone to the curb, and in that sense, the question is, where exactly do these allegations fall?”

Lawyers for Turkey say in court papers that the melee began when security officers were confronted by an “encroaching group of apparent terrorist supporters and/or sympathizers” who had already defied the commands of local police officers. The lawyers accuse the other side of “overly broad sermonizing” and say they intend to rebut what they see as unfair criticism of Turkish governance and allegations of human rights atrocities.

Even in an embassy-packed capital where protests are common, including outside the foreign residences that line Washington’s Massachusetts Avenue, the altercation stood out for vivid scenes of violence captured on camera and repeatedly broadcast on TV. Many who say they were injured are American citizens, including some who were there with their young children.

It all began as Erdogan was returning to the ambassador’s residence after a White House visit, where he and Trump pledged cooperation in fighting the Islamic State group.

Security officers for Erdogan, including some armed and dressed in military-style clothing, clashed with protesters denouncing Turkey’s treatment of its Kurdish minorities and its policies in Syria and Iraq. Plaintiffs in two separate suits say they were brutally punched and kicked, cursed at, and greeted with slurs and throat-slashing gestures. One woman slipped in and out of consciousness and has suffered seizures, and others reported post-traumatic stress, depression, concussions and nightmares, according to the complaints.

Erdogan remained in his car after it arrived at the ambassador’s residence, and after conferring with the head of his security detail, ordered a second attack, the suits allege.

U.S. lawmakers swiftly condemned the violence, writing letters to the departments of State and Justice, and urging the Trump administration to hold the attackers legally accountable.

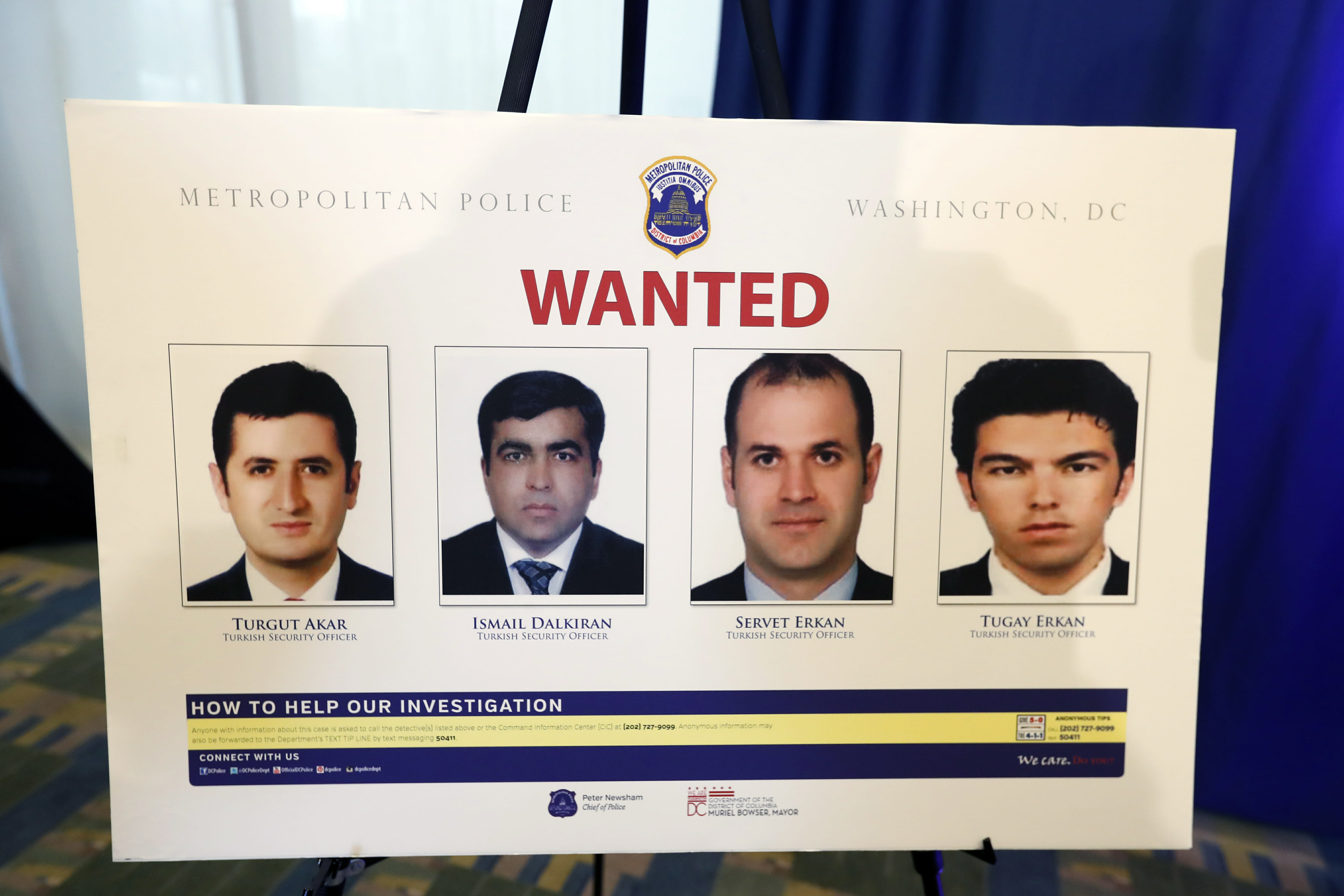

Prosecutors in Washington initially charged 19 people, including 15 security officers for Erdogan. Two civilians pleaded guilty, but many of the other cases have since been dismissed, with defendants leaving the U.S. after the brawl, according to court papers.

Foreign governments are generally immune from being sued in American courts, but there are multiple exceptions, including for terrorism and other actions that cause injury for which financial damages are sought.

Diplomats and other agents of foreign governments have in the past been held accountable for bad behavior in the U.S., though some of the more memorable cases have involved nonofficial duties such as fatal drunken driving crashes. A Georgian Embassy official, for instance, was sentenced to prison in 1997 for a drunken driving crash that killed a teenage girl.

In perhaps the most recent analogous case, a judge entered a default judgment against the Congolese government after it failed to respond to a suit from a protester who said he was badly beaten in 2014 outside a Washington hotel by security officers for President Joseph Kabila. The individual security officers who were sued later sought to vacate that default judgment, and a judge dismissed claims against Kabila.

Turkey, meanwhile, has said for months through its lawyers that it intends to aggressively contest the allegations, and both lawsuits name the country as a defendant. One separately includes as defendants five U.S. and Canadian citizens accused in the attacks. A judge has permitted most of the claims against the defendants, who are not Turkish government officials, to move forward.

Lawyers for the protesters see an opportunity to hold the Turkish government accountable for the violence.

“It’s important to protect people’s First Amendment rights and the freedom of expression. It’s important to show that the United States stands up for those rights,” Fryszman said.

The Western Journal has not reviewed this Associated Press story prior to publication. Therefore, it may contain editorial bias or may in some other way not meet our normal editorial standards. It is provided to our readers as a service from The Western Journal.

Truth and Accuracy

We are committed to truth and accuracy in all of our journalism. Read our editorial standards.

Advertise with The Western Journal and reach millions of highly engaged readers, while supporting our work. Advertise Today.