Flashback: The Time SCOTUS Officially Declared the US a Christian Nation

When an ordinary public official refers to the United States as “a Christian nation,” the reference conveys an opinion.

When the United States Supreme Court uses this same phrase, however — and when the phrase serves as the primary justification for a unanimous decision that overturns a lower-court ruling — the phrase suddenly carries the weight of judicial precedent.

This is precisely what occurred the 1892 case Church of the Holy Trinity v. United States.

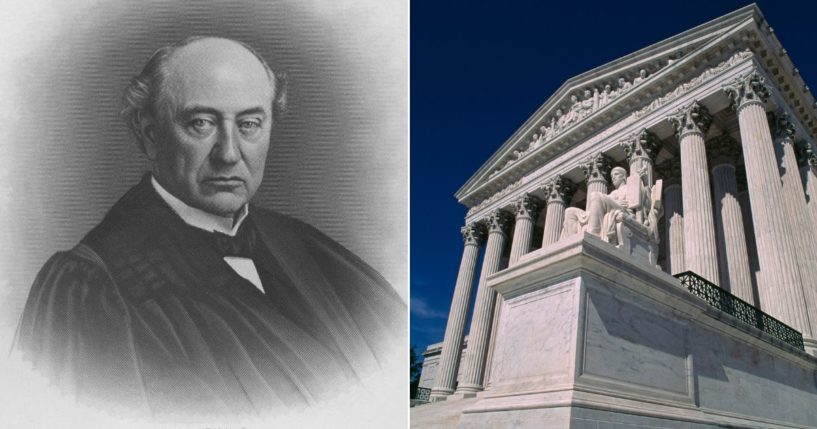

Justice David J. Brewer wrote the opinion in a case noteworthy both for the Court’s unanimity and for its reasoning.

Oddly enough, Church of the Holy Trinity v. United States originated in a dispute over labor law.

In 1887, the New York-based Church of the Holy Trinity contracted with E. Walpole Warren, a resident of England. By the terms of the contract, Warren would relocate to New York and serve as the church’s rector and pastor.

Alas, in 1880 the U.S. Congress had passed legislation “to prohibit the importation and migration of foreigners and aliens under contract or agreement to perform labor in the United States, its Territories, and the District of Columbia.” A lower court ruled that Warren’s contract with the church violated the 1880 law.

Significantly, Brewer did not dispute the lower court’s literal reading of that 12-year-old statute.

“It must be conceded that the act of the corporation is within the letter of this section, for the relation of rector to his church is one of service, and implies labor on the one side with compensation on the other,” Brewer wrote.

Furthermore, the fifth section of the 1880 law made “specific exceptions,” and “rector” or “pastor” did not appear among them.

Having acknowledged the lower court’s firm literal ground, Brewer nonetheless explained that the Supreme Court had reached a different conclusion.

“While there is great force to this reasoning, we cannot think Congress intended to denounce with penalties a transaction like that in the present case,” Brewer wrote.

In other words, Warren’s contract with the Church of the Holy Trinity involved special considerations.

One such consideration involved context. For instance, every piece of contemporary evidence showed that in 1880, Congress sought to prevent the influx of cheap and unskilled foreign laborers — those who, by contracting with U.S. employers, suppressed the demand for native workers. Citing “intent of the legislature,” Brewer noted that Congress did not mean to exclude preachers.

Brewer, however, did not rest his opinion on “intent of the legislature.” He went further.

“But, beyond all these matters, no purpose of action against religion can be imputed to any legislation, state or national, because this is a religious people,” he wrote.

In short, no government at any level may take “action against religion,” because Americans are “a religious people.” One can scarcely imagine a stronger assertion of religious liberty rooted in tradition.

Brewer then reviewed the history of explorers’ commissions, colonial charters, grants of privileges, state constitutions and other solemn public declarations since Christopher Columbus’ time. All “affirm and reaffirm that this is a religious nation,” he wrote.

Furthermore, “American life, as expressed by its laws, its business, its customs, and its society,” reveals “the same truth.” In fact, “These, and many other matters which might be noticed, add a volume of unofficial declarations to the mass of organic utterances that this is a Christian nation.”

Thus, because America is “a Christian nation,” could anyone reasonably assume that Congress “intended to make it a misdemeanor for a church of this country to contract for the services of a Christian minister residing in another nation?”

No one could mistake the basis of Brewer’s reasoning. Indeed, he devoted more than half of the opinion to centuries of evidence revealing America as “a Christian nation.”

Legal scholars refer to extraneous judicial editorializing as obiter dictum — personal views devoid of legal force. Brewer’s opinion, however, does not qualify as obiter dictum.

The Supreme Court ruled that the 1880 statute did not prohibit the church’s contract with Warren. It based that ruling on the “intent of the legislature” derived from America’s identity as “a Christian nation.” That Christian identity, therefore, represents the most important point in the entire case.

Congress might ban foreign contract labor, but it would not dare exclude rectors and pastors. Elected representatives in “a Christian nation” would never dream of such a thing.

So the Supreme Court once ruled.

Truth and Accuracy

We are committed to truth and accuracy in all of our journalism. Read our editorial standards.

Advertise with The Western Journal and reach millions of highly engaged readers, while supporting our work. Advertise Today.